Bulls and Briefs

A bulla

was originally a circular plate or boss of metal, so called from its

resemblance in form to a bubble floating upon water (Latin bullire,

to boil). In the course of time the term

came to be applied to the leaden seals

with which papal and royal

documents were authenticated in the early Middle Ages,

and by a further development, the name, from designating the seal, was

eventually attached to the document itself. This did not happen before the

thirteenth century and the name bull was only a popular term used

almost promiscuously for all kinds of instruments which issued from the papal chancery.

A much

more precise acceptance has

prevailed since the fifteenth century, and a bull has long stood in sharp

contrast with certain other forms of papal

documents.

For

practical purposes a bull may be conveniently defined to be "an Apostolic letter

with a leaden seal," to

which one may add that in its superscription the pope

invariably takes the title of episcopus, servus servorum Dei.

In

official language papal documents

have at all times been called by various names, more or less descriptive of

their character. For

example, there are "constitutions," i.e., decisions addressed to

all the faithful and determining some matter of faith or discipline;

"encyclicals," which are letters sent to all the bishops of Christendom,

or at least to all those in one particular country, and intended to guide

them in their relations with their flocks; "decrees,"

pronouncements on points affecting the general welfare of the Church; "decretals"

(epistolae decretales), which are papal replies

to some particular difficulty submitted to the Holy See, but

having the force of precedents to rule on all analogous cases.

"Rescript,"

again, is a form applicable to almost any form of Apostolic letter

which has been elicited by some previous appeal, while the nature of a

"privilege" speaks for itself.

But all

these, down to the fifteenth century, seem to have been expedited by the papal chancery in the

shape of bulls authenticated with leaden seals, and it

is common enough to apply the term bull even to those very early papal letters

of which we know little

more than the substance, independently

of the forms under which they were issued.

It will

probably be most convenient to divide the subject into periods, noting the

more characteristic features of papal documents in each age.

|

Una bula era originalmente una placa o un jefe circular del

metal, supuesto de su semejanza en forma a una burbuja que flotaba sobre el

agua (bullire latino, hervir). En el curso de tiempo el término vino ser

aplicado a los sellos de plomo con los cuales los documentos papales y reales

fueron autenticados en la edad media tempranas, y por otro desarrollo, el

nombre, de señalar el sello, fue unido eventual al documento sí mismo. Esto no

sucedió antes del siglo 13 y bula conocido era solamente un término popular

usado casi promiscuo para todas las clases de instrumentos que publicaron de

la cancillería papal.

Una aceptación mucho más exacta ha prevalecido desde el siglo

15, y una bula ha estado usando de largo en contraste agudo con ciertas otras

formas de documentos papales.

Para los propósitos

prácticos una bula puede ser definido convenientemente para ser “una letra

apostólica con un sello de plomo,” a cuál puede agregar uno que en su superscription el papa toma

invariable el título del episcopus,

servus servorum Dei.

En lengua oficial los documentos papales han sido llamados

siempre por varios nombres, más o menos descriptivo de su carácter. Por

ejemplo, hay “constituciones,” es

decir, decisiones tratadas a todo fieles en una determinar

materia de fe o de la

disciplina; “encíclicas,” que son

letras enviaron a todos los obispos de la cristiandad, o por lo menos a todo

de un país particular, y se prepusieron dirigirlo en sus relaciones con sus

multitudes; “decretos,”

declaraciones en los puntos que afectan el bienestar general de la iglesia;

los “decretals” (epistolae

decretales), que son contestaciones papales a una cierta

dificultad particular sometieron

“Rescripto,” otra

vez, es una forma aplicable a casi cualquier forma de letra apostólica que ha

sido sacada por una cierta súplica, mientras que la naturaleza de un

“privilegio” habla para sí mismo.

Pero todo el éstos, tragan al siglo 15, se parecen haber sido apresurados

por el cancillería papal en la forma de bulas autenticados con los sellos de

plomo, y es bastante común aplicar a bulas del término incluso a esas letras

papales muy tempranas de las cuales sepamos poco más que la sustancia,

independientemente de las formas bajo las cuales fueron publicadas.

Será probablemente el más conveniente dividir el tema en los períodos, observando las características de documentos papales en cada edad. |

I. EARLIEST TIMES TO

|

I. ÉPOCAS MÁS TEMPRANAS a PAPA ADRIANO I

(772)

No puede haber duda que la formación de una

cancillería o de una oficina para preparar los papeles oficiales era un

trabajo del tiempo.

Desafortunadamente,

los documentos papales más tempranos sabidos a nosotros se preservan

solamente en las copias o los extractos de los cuales es difícil dibujar

cualquier conclusión segura en cuanto a las formas observadas en publicar las

originales.

Para todo el eso, es prácticamente cierto

que ningunas reglas uniformes se pueden haber seguido en cuanto al

superscription, la fórmula del saludo, la conclusión, o la firma.

Era

solamente cuando una cierta clase de registro fue organizada, y las copias de

la correspondencia oficial anterior llegaron a estar disponibles, que una

tradición creció gradualmente para arriba de ciertas formas acostumbradas de

las cuales no ought ser salido.

A

excepción de la mención insatisfactoria de un cuerpo de notarios cargó con

guardar un expediente de los actos de los Martyrs, C. 235 (Duchesne, Liber

Pontificalis, I, Pp. c-c1), nosotros resuelven sin referencia clara a los

archivos papales hasta la época de papa Julio I (337-353), aunque en el pontificado

de Damasco, antes del final del mismo siglo, allí es mención de un edificio

apropiado a este propósito especial.

Aquí,

en el scrinium, or archivium sanctæ

Romanæ ecclesiæ los documentos se deben todavía haber

colocado y haber mantenido una orden definida, porque extractos y copias en

rastros del coto de la existencia de su enumeración. Estas colecciones o el regesta fueron de nuevo a la época de

papa Gelasius (492-496) y probablemente anterior.

En la correspondencia de papa Hormisdas

(514-525) hay indicaciones de un cierto endoso oficial que registra la fecha

en la cual las letras te trataron fueron recibidas, y por la época de San

Gregorio el grande (590-604) Ewald ha sido por lo menos parcialmente acertado

en la reconstrucción de los libros que contuvieron las copias de las cartas

del papa.

Puede haber poco duda que el cancillería

Pontifical de el cual deducimos así la existencia fue modelado sobre el de la

corte imperial.

El scrinium,

los notarios regionales, los funcionarios más altos tales como el primicerius y el secundarius, el arreglo del Regesta por indictions, etc., son todo probablemente las imitaciones de la

práctica del bajo imperio.

Por lo tanto podemos deducir que el código

de formas reconocidas pronto se estableció, análogo a eso observado por los

notarios imperiales.

Un

formulario de esta descripción probablemente todavía se preserva a nosotros

en el libro llamado “Liber Diurnus”, el bulto de el cual se parece ser

inspirado por la correspondencia oficial de papa Gregorio el grande.

En las letras papales anteriores, sin

embargo, hay hasta ahora solamente pocas muestras de la observancia de formas

tradicionales.

El

documento nombra a veces a papa primero, a veces el destinatario. Para la

mayor parte el papa no lleva ningún título excepto Sixtus episcopus or Leo

episcopus catholicae ecclesiæ, a veces, sino

que más raramente te llaman Papa.

Debajo

de Gregorio el grande servus servorum Dei

fue agregado a menudo

después de episcopus -- Gregorio,

es dicho, seleccionando esta designación como protesta contra la arrogancia

del patriarca de Constantinopla, John

the Faster, que se llamó “obispo ecuménico.”

Pero aunque varios de sucesores del San

Gregorio lo siguieron en esta preferencia, no era hasta el siglo 9 que la

frase vino ser utilizada invariable en documentos del momento.

Antes de que encontraran a papa Adeodatus

(elegido 672) pocos saludos, solamente él utilizó la forma “"salutatem a Deo et

benedictionem nostram." La frase ahora consagrada “salutatem et apostolicam

benedictionem” ocurre apenas siempre antes del siglo

10.

Un

bula falsa engañaron a los autores benedictinos de “Nouveau traité de diplomatique” en la atribución de una fecha

mucho anterior a este fórmula que pretendía ser tratado al monasterio en San

Benignus en Dijon.

Una vez más en éstos las letras tempranas el

papa se dirigió a menudo a su correspondiente, más especialmente cuando él

era rey o una persona de la alta dignidad, por el nos plural.

Mientras que se pasaba la edad, ésta llegó a

ser más rara, y por la segunda mitad del siglo 12, había desaparecido

totalmente.

Por otra parte, puede ser notado incidentemente que

las personas de todas las filas, en escribir al papa, se dirigieron invariable

a él como nos. Un saludo fue introducido a veces por el papa en el extremo de

su letra momentos antes de la fecha--por ejemplo, "Deus te incolumem custodiat" or "Bene vale frater

carissime."

Este saludo final era una cuestión de

importancia, y es llevado a cabo por las altas autoridades (Bresslau, “und Pergament, 21 del papiro;

Ewald en Neues Archiv,” III, 548) ese fue agregado en propia mano del

papa, y eso era el equivalente de su firma.

El

hecho que en épocas clásicas los romanos autenticó sus letras no firmando sus

nombres, pero por una palabra del adiós, presta probabilidad a esta visión.

En las bulas originales más tempranos

preservados a nosotros BENE VALETE se escribe en integral en capitales. Por

otra parte, tenemos por lo menos cierta evidencia contemporánea de la

práctica antes de la época de papa Adriano.

El

texto de una letra de papa Gregorio el grande se preserva en una inscripción

de mármol en la basílica de San Paul fuera de las paredes.

Como

la letra dirige que el documento sí mismo es ser

vuelto a los archivos papales (Scrinium), nosotros puede asumir que la copia

en piedra representa exactamente la original. Se trata a Felix el sub. diacono

y concluye con el fórmula BENE VALE. Dat. VIII

Kalend. Februarius imp. du. n. Phoca PP. anno secundo, et consultatus eius

anno primo, indict. 7.

Esto sugiere que tales letras

fueran completamente anticuadas y encontramos de hecho rastros de fechar

incluso en copias extraídas desde la época de papa Siricius (384-398).

Tenemos también algún bullæ o sellos de plomo preservados aparte de los

documentos a los cuales fueron unidas una vez. Uno de éstos dató quizás del pontificado

de Juan III (560-573) y otro pertenece ciertamente a Deusdedit (615-618).

Los especimenes más tempranos llevan simplemente el nombre del

papa en un lado y el papæ de la palabra en el otro.

|

II. SECOND PERIOD (772-1048)

In the time of Pope Adrian

the support of Pepin and Charlemagne

had converted the patrimony of the Holy See

into a sort of principality. This no doubt

paved the way for changes in the forms observed in the chancery.

The pope now takes

the first place in the superscription of letters unless they are addressed to

sovereigns. We also find the leaden seal

used more uniformly.

But

especially we must attribute to the time

of

The other, beginning with Data (in

later ages Datum), indicated, with a new and more detailed specification

of year and day, the name of the dignitary who issued the bull after it had

received its final stamp of authenticity

by the addition of the seal.

The pope still

wrote the words BENE VALETE in capitals with a cross before and after, and in

certain bulls of Pope Sylvester II

we find some few words added in shorthand or "Tyronian notes."

In other

cases the BENE VALETE is followed by certain dots and by a big comma, by a S

S (subscripsi), or by a flourish, all of which no doubt served as

a personal authentication.

To this period belong the earliest extant

bulls preserved to us in their original shape.

They are all written upon very large sheets

of papyrus in a peculiar handwriting of the

The

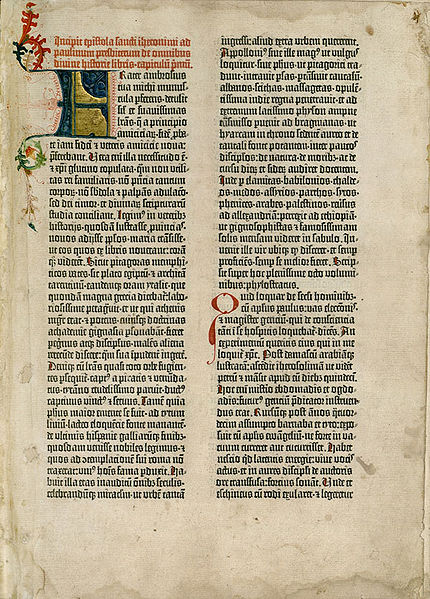

annexed copy of a facsimile in Mabillion's "De re diplomaticâ"

reproducing part of a bull of Pope Nicolaus

I (863), with the editor's interlinear decipherment, will serve to give an idea of the

style of writing.

As these

characters were even then not easily read outside of Italy it seems

to have been customary in some cases to issue at the same time a copy

upon parchment in ordinary minuscule. A French writer of the tenth century

speaking of a privilege obtained

from Pope Benedict VII

(975-984) says that the petitioner going to Rome obtained

a decree duly

expedited and ratified by apostolic

authority, two copies of which, one in our own character (nostra

littera) on parchment, the other in the Roman character on

papyrus, he deposited on his return in our archives. (Migne, P. L.,

CXXXVII, 817) Papyrus seems to have been used almost uniformly as the

material for these official documents until the early years of the eleventh

century, after which it was rapidly superseded by a rough kind of parchment.

Apart from

a small fragment of a bull from Adrian I (22

January, 788) preserved in the national library at Paris, the

earliest original bull that remains to us is one of Pope Paschal I

(11 July, 819).

It is

still to be found in the capitular archives of Ravenna, to which

church it was originally addressed. The total number of papyrus bulls at

present known to be in existence is

twenty-three, the latest being one issued by Benedict VIII

(1012-24) for the monastery of Hildesheim.

All these documents at one time had

leaden seals appended

to them, though in most cases these have disappeared.

The seal was

attached with laces of hemp and it still bore only the name of the pontiff

and the word papæ on the other. After the year 885, the letters of the

pope's name were

usually stamped round the seal in a

circle with a cross in the middle.

The

details specified in the "double dates"

of these early bulls afford a certain amount of indirect information about

the personnel of the papal chancery. The

phrase scriptum per manum is vague and leaves uncertain whether the person mentioned

was the official who drafted or merely engrossed the bull, but we hear in

this connection of persons described

as notarius, scriniarius (archivist), proto scrinarius sanctæ

Romanæ ecclesiæ, cancellarius, ypocancellarius, and after 1057 of camerarius,

or later still notarius S. palatii.

On the

other hand, the datarius, the official mentioned under the heading data,

who presumably delivered the instrument to the parties, after having

superintended the subscriptions and the apposition of the seal, seems to

have been an official of still higher consequence.

In earlier

documents he bears the titles primicerius sanctæ sedis apostolicae, senior

et consiliarius, etc., but as early as the ninth century we have the

well-known phrase bibliothecarius sanctæ sedis apostolicæ, and later cancellarius

and bibliothecarius, as a combined title borne by a cardinal, or

perhaps by more than one cardinal at once.

Somewhat later still (under Innocent III),

the cancellarius seemed to have threatened to develop into a functionary who

was dangerously powerful, and the office was suppressed.

A

vice-chancellor remained, but this dignity also was abolished before 1352.

But this of course was much later than the period we have now reached.

|

II. SEGUNDO PERÍODO

(772-1048)

En la época de papa Adriano la ayuda de Pipino el

Breve y de Carlomagno había convertido el patrimonio de

El papa ahora toma el primer lugar en el superscription de letras a menos que se traten a los soberanos.

También encontramos el sello de plomo utilizamos más uniformemente.

Pero especialmente debemos atribuir a la época de Adriano la

introducción de la “fecha doble” endosada en el pie de bula. La primera fecha

comenzó con la palabra Scriptum y

después de una entrada cronológica, que mencionó solamente el mes y el indiction, agregó el nombre del

funcionario que bosquejó o elaboro el documento.

El otro, comenzando con los datos (en un dato más último de las

edades), indicados, con una nueva y más detallada especificación del año y

del día, el nombre del dignatario que publicó el toro después de él había

recibido su estampilla final de la autenticidad por la adición del sello.

El papa todavía escribió las palabras BENE VALETE en capitales

con una cruz antes y después, y en ciertas bulas de papa Sylvester II encontramos algunas pocas palabras agregadas en

taquigrafía o las “notas Tyronian.”

En otros casos el BENE

VALETE es seguido por ciertos puntos y por una coma grande, por un S S (subscripsi), o por un prosperar, que

ninguna duda sirvió como autentificación personal.

A este período pertenecen las bulas más tempranas preservadas a

nosotros en su forma original.

Bulas todas escriben sobre las hojas muy grandes del papiro en

un cursivo peculiar del tipo Lombardo, llamado a veces littera romana.

La copia anexada de un facsímil

en Mabillion

del “De re diplomaticâ” de la

reproducción de una bula de papa

Nicolaus I (863), con el desciframiento interlineal del redactor, servirá

para dar una idea del estilo de la escritura.

Pues estos caracteres eran uniformes entonces leídos no

fácilmente fuera de Italia se parece haber sido acostumbrado en algunos casos

publicar al mismo tiempo una copia sobre el pergamino en minúscula ordinario.

Un escritor francés del discurso del siglo 10 de un privilegio obtenido de

papa Benedicto VII (975-984) dice que el solicitante que iba a Roma obtuvo un

decreto debido apresurado y ratificado por autoridad apostólica, dos copias

de las cuales, una en nuestro propio carácter (nostra littera ) en el

pergamino, el otro en el carácter romano en el papiro, él depositó en su

vuelta en nuestros archivos. (Migne,

P.L., CXXXVII, 817) el papiro se parece haber sido utilizado casi

uniformemente como el material para estos documentos oficiales hasta los años

del siglo 11, después de lo cual fue

reemplazado rápidamente por una clase áspera de pergamino.

Aparte de un fragmento pequeño de un bula de Adriano I (el 22 de

enero de 788) preservado en la biblioteca nacional en París, la bula original

más temprano que permanece a nosotros es uno de papa Paschal I (el 11 de

julio de 819).

Debe todavía ser encontrado en los archivos capitular de Ravena,

que a iglesia fue tratado originalmente. El número total de los bulas del

papiro sabidos actualmente para estar en existencia es veintitrés, el ser más

último una publicada por Benedicto VIII (1012-24) para el monasterio de

Hildesheim.

Todos estos documentos contemporáneamente tenían sellos de plomo

añadidos a ellos, aunque en la mayoría de los casos han desaparecido éstos.

El sello fue unido con

los cordones del cáñamo y todavía agujerea solamente el nombre del

pontificado y el papæ de la palabra en el otro. Después del año 885, las

letras del nombre del papa fueron estampadas generalmente alrededor del sello

en un círculo con una cruz en el centro.

Los detalles especificados en las “fechas dobles” de estas bulas

tempranos producen cierta cantidad de información indirecta sobre el personal

del cancillería papal.

El scriptum de la frase scriptum per manum y se va incierto si la persona mencionada era el funcionario

que bosquejó o absorbió simplemente la bula, pero oímos a este respecto de

las personas descritas como notarius,

scriniarius

(archivist), proto scrinarius sanctæ Romanæ ecclesiæ, cancellarius,

ypocancellarius, y después de 1057 del camerarius, o de un notarius S. palatii inmóvil más último.

Por otra parte, el

datarius, el funcionario mencionado bajo datos del título, que entregaron

probablemente el instrumento a los partes, después teniendo superintendencia

las suscripciones y la aposición del sello, se parece haber sido un funcionario

de la consecuencia más alta inmóvil.

En documentos anteriores él

lleva los títulos primicerius sanctæ sedis

apostolicae, senior et consiliarius,, el etc., pero desde el

noveno siglo 9 tenemos el sedis

apostolicæ bien conocido, del sanctæ de la frase, y un cancellarius y un

bibliothecarius más últimos, pues un título combinado llevado por un

cardenal, o quizás por más que uno cardinal inmediatamente. Algo más adelante

aún (debajo de Innocent III), el cancellarius se parecía haber amenazado convertirse

en un funcionario que era peligroso de gran alcance, y la oficina fue

suprimida.

Un vice-chancellor

permanecía, pero esta dignidad también fue suprimida antes de 1352. Pero esto

por supuesto era mucho más adelante que el período que ahora hemos alcanzado.

|

III. THIRD PERIOD (1048-1198)

The accession of Leo IX, in 1048,

seems to have inaugurated a new era in the procedure of the chancery.

A definite

tradition had by this time been created, and

though there is still much development we find uniformity of usage in

documents of the same nature. It is at

this point that we begin to have clear distinctions between two classes of

bulls of greater and less solemnity.

The Benedictine

authors of "Nouveau traité de diplomatique" call them great and

little bulls. Despite a protest in modern times from M. Léopold Delisle, who

would prefer to describe the former class as "privileges" and the

latter as "letters," this nomenclature has been found sufficiently

convenient, and it corresponds, at any rate, to a very marked distinction

observable in the papal documents

of the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries.

The most

characteristic features of the "great bulls" are the following:

The pope has no

cross before his name; the cardinals have.

Earlier than this, even the great bulls were subscribed by the pope alone,

unless they embodied conciliar or

consistorial decrees, in which

case the names of cardinals and bishops were also

appended.

In this

the outer portion of the wheel is formed by two concentric circles and within

the space between

these circles is written the pope's signum

or motto, generally a brief text of scripture

chosen by the new pontiff at the

beginning of his reign.

Thus Leo IX's

motto was "Miseracordia domini plena est terra," Adrian IV's

"Oculi mei semper ad dominum." Before the words of the motto a

cross is always marked, and this is believed

to have been traced by the hand of the pope

himself.

Not only

in the case of the pope, but even

in the case of the cardinals, the

signatures appear not to have been their own actual handwriting. In the

center of the rota we have the names of Sts. Peter and Paul, above and

beneath them the name of the reigning pope.

An example from a bull of Adrian IV will make

the matter clear: "Datum Laterani per manu Rolandi sanctæ Romanæ

ecclesiæ presbyteri cardinalis et cancellarii, XII Kl. Junii, indic. Vo, anno

dominicae incar. MCLVIIo pontificatus vero domini Adriani papæ quarti anno

tertio."

Before

this period it was also usual to insert the first dating clause,

"Scriptum," and there was sometimes an interval of a few days

between the "Scriptum" and the "Datum."

The

use of the double date, however,

soon came to be neglected even in "great bulls" and before 1124 it

had gone out of fashion. This was probably a result of the general employment

of "little bulls," the more distinctive features of which may now

be specified.

The

purpose served by this distinction between the great and little bulls becomes

tolerably clear when we look more narrowly into the nature of their

contents and the procedure followed in expediting them.

Excepting those which are concerned with

purposes of great solemnity or public

interest, the majority of the "great bulls" now in existence are in

the nature of

confirmations of property or

charters of protection accorded to monasteries

and religious institutions.

At an epoch when there was much fabrication

of such documents, those who procured bulls from Rome wished at

any cost to secure that the authenticity

of their bulls should be above

A

papal confirmation,

under certain conditions, could be pleaded as itself constituting sufficient

evidence of title in cases where the original deed had been lost or

destroyed.

Now

the "great bulls" on account of their many formalities and the

number of hands they passed through, were much more secure from fraud of all

kinds, and the parties interested were probably willing to defray the

additional expenditure that might be entailed by this form of instrument.

On

the other hand, by reason of the same multiplication of formalities, the drafting,

signing, stamping, and delivery of a great bull was necessarily a matter of

considerable time and

labor.

The

little bulls were much more expeditious. Hence we are confronted by the

curious anomaly that during the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries,

when both forms of document were in use, the contents of the little bulls

are, from an historical point of view immensely more interesting and

important than those of the bulls in solemn form.

Of

course the little bulls may themselves be divided into various categories.

The distinction between litteræ communes

and curiales seems rather to have belonged to a later period, and to

have rather concerned the manner of entry in the official "Regesta,"

the communes being copies into the general collection, the curiales

into a special volume in which documents were preserved which by reason of

their form or their contents stood apart from the rest.

We

may note, however, the distinction between tituli and mandamenta.

The tituli were letters of a gracious character--donations, favors,

or confirmations constituting a "title."

They were indeed little bulls and lacked the

subscriptions of cardinals, the rota

etc., but on the other hand, they preserved certain features of solemnity.

Brief

imprecatory clauses, like Nulli ergo, Si quis autem, are usually

included, the pope's name at

the beginning is written in large letters, and the initial is an ornamental

capital, while the leaden seal is

attached with silken laces of red and yellow.

As

contrasted with the tituli, the mandamenta, which were the

"orders," or instructions, of the popes, observe

fewer formalities, but are more business-like and expeditious.

They

have no imprecatory clauses, the pope's

name is written with an ordinary capital letter, and the leaden seal is

attached with hemp.

But

it was by means of these little bulls, or litteræ, and notably of the mandamenta,

that the whole papal

administration, both political and religious, was conducted. In particular,

the decretals, on which

the whole science of

Canon Law is built up, invariably took this form.

|

III. TERCER PERÍODO

(1048-1198)

La accesión del León IX, en 1048, se parece haber inaugurado una

nueva era en el procedimiento de la cancillería.

Una tradición definida por este tiempo había sido creada, y

aunque todavía hay mucho desarrollo nosotros encuentra la uniformidad del uso

en documentos de la misma naturaleza. Es a este punto que comenzamos a tener

distinciones claras entre dos clases de bulas de mayor y de menos solemnidad.

Los autores benedictinos de “Nouveau

traité de diplomatique” los llaman los grandes y pequeñas bulas. A pesar

de una protesta en épocas modernas del M.

Léopold Delisle, que preferiría describir la clase anterior como

“privilegios” y el último como “letras,” esta nomenclatura se ha encontrado

suficientemente conveniente, y corresponde, de todos modos, a un observable

muy marcado de la distinción en los documentos papales de los siglos 11, 12.y 13.

Las características de los “grandes bulas” son las

siguientes:

1º. En el superscription el servus servorum de las palabras es seguido por una cláusula de la perpetuidad,

e.g., en el perpetuam memoriam

(abreviado en IN PP. M) o Ad perpetuam

memoriam rei. En contraste con esto los pequeños bulas tienen generalmente,

con las palabras salutatem

et apostolicam benedictionem también aparecen en algunos grandes toros

después de la cláusula de la perpetuidad.

2º. Después del segundo trimestre del siglo 12, los grandes bulas

fueron suscritos siempre por el papa y algunos cardenales (obispos,

sacerdotes, y diáconos). Los nombres de los cardinal-obispos se escriben en

el centro, debajo del papa; los de cardinal-sacerdotes a la izquierda, y los

de cardinal-diáconos a la derecha, mientras que un espacio en blanco

ocasional demuestra que el espacio se ha dejado para el nombre de un cardenal

que no pudo accidentalmente estar presente.

El papa no tiene ninguna cruz antes de su nombre; los cardenales

tienen. Anterior que esto, incluso los grandes toros fueron suscritos por el

papa solamente, a menos que incorporaran los decretos conciliar o consistorial, en este caso los nombres de

cardenales y de obispos también fueron añadidos.

3º. En el pie del documento a la izquierda de la firma del papa se

coloca la rota o la rueda.

En esto la porción

externa de la rueda es formada por dos círculos concéntricos y dentro del

espacio entre estos círculos se escribe el signum o el lema, generalmente un breve texto del papa de scripture elegido por el nuevo

pontífice al principio de su reinado.

Así el León IX el lema de

era “"Miseracordia domini plena est terr,” Adriano IV “.Oculi

mei semper ad dominum.” Antes de las palabras del lema una cruz está marcada siempre,

y esto se cree para haber sido remontada por la mano del papa misma.

No sólo en el caso del papa, pero igualar en el caso de los

cardenales, las firmas aparecen no haber sido tu propio cursivo real. En el

centro de la rota tenemos los nombres del Sts. Peter y Paul, sobre y debajo

de ellos el nombre del papa reinante.

4º. A la derecha de la firma enfrente de la rota está parado el

monograma que está parado para Bene

Valete. Desde León IX, y posiblemente algo anterior, las palabras nunca

se escriben por completo, sino como una clase de grotesco. Se parece claro

que el Bene Valete debe no más ser

mirado como el equivalente de la firma o de la autentificación del papa. Es

simplemente una supervivencia interesante de una forma anterior de saludo.

5º.- En lo que concierne al cuerpo del documento, la letra del papa,

en el caso de grandes bulas termina siempre con cierto imprecatory y prohibitorias cláusulas, Decernimus ergo, etc., Siqua igitur,

etc por otra parte, de Cunctis autem,, etc., es un fórmula de la bendición. Este y las cláusulas de

los similares están generalmente ausentes de los “pequeños bulas,” pero

cuando aparecen--y esto sucede a veces--la fraseología usada es algo

diferente.

6º.-el siglo 11 era generalmente escribir Amen en el extremo del

texto de un bula tanto tiempo cuanto

sea necesario para llenar para arriba la línea.

7º.-la adición de la fecha, o más exacto, en la adición de la

cláusula que comienza fecha, el costumbre era incorporar el lugar, el nombre

del datarius, el día del mes

(expresado según el método romano) el

indiction, el año de Incarnation

de nuestro señor, y el año del reinado del pontífice, que es mencionado por

su nombre.

Un ejemplo de un toro de Adriano IV hará el claro de la materia:

"Datum Laterani per manu Rolandi sanctæ Romanæ ecclesiæ presbyteri

cardinalis et cancellarii, XII Kl. Junii, indic. Vo, anno dominicae incar.

MCLVIIo pontificatus vero domini Adriani papæ quarti anno tertio."

Antes de que este período fuera también generalmente insertar la primera cláusula que fechaba, “Scriptum,” y había a veces un intervalo de algunos días entre el “Scriptum” y el “datum.”

El uso de la fecha doble,

sin embargo, pronto vino ser descuidado incluso en “grandes bulas” y antes de

1124 había salido de la manera. Éste era probablemente un resultado del empleo

general de los “pequeños bulas,” las características más distintivas de los

cuales pueden ahora ser especificadas.

1º.- Aunque los grandes y pequeños bulas comienzan igualmente con el

nombre del papa- Urbanius, dejó a nos decir,, “episcopus, servorum servus Dei”--en los pequeños bulas no tenemos

ninguna cláusula de la perpetuidad, sino” "salutatem et apostolicam benedictionem

2º.- Los

fórmulas del imprecation, del etc.,

en el extremo ocurren solamente por la excepción, y son en todo caso más exactos

que los de los grandes bulas

3º.- Los pequeños toros no tienen ningún rota, ningún monograma de Bene Valete y ninguna suscripción del

papa y de cardenales

. Propósito servido por esta distinción entre

los grandes y pequeños bulas llega a estar tolerable claro cuando miramos más

estrecho en la naturaleza de su contenido y del procedimiento seguido en

apresurarlos.

Excepto

las que se refieran a propósitos del gran interés de la solemnidad o del

público, la mayoría de los “grandes bulas” ahora en existencia está de forma

de confirmaciones de la característica o de cartas de la protección acordadas

a los monasterios y a las instituciones religiosas.

En

una época cuando había mucha falsificación de tales documentos, los que procuraron bulas

de Roma deseaban en cualquier coste asegurar que la autenticidad de sus bulas

debe estar por encima de toda sospecha.

Una

confirmación papal, bajo ciertas condiciones, se podría abogar por como sí

mismo que constituía la suficiente evidencia del título en caso de que el

hecho original hubiera sido perdido o destruido.

Ahora los “grandes bulas” a causa de sus

muchas formalidades y del número de manos que pasaron a través, eran mucho

más seguras del fraude de todas las clases, y los partidos interesados

estaban probablemente dispuestos a pagar el gasto adicional que se pudo

exigir por esta forma de instrumento.

Por

otra parte, por causa de la misma multiplicación de formalidades, el

bosquejo, la firma, el estampar, y la entrega de una gran bula necesariamente

una cuestión de tiempo y de trabajo considerables.

Los

pequeños bulas eran mucho más expeditivos. Por lo tanto la anomalía curiosa

que durante los siglos 11, 12 y 13, cuando ambas formas de documento eran

funcionando, el contenido de los pequeños bulas es, desde un punto de vista

histórico nos enfrentamos inmenso más interesante e importante que los de los

bulas en forma solemne.

Por

supuesto los pequeños bulas pueden ellos mismos ser divididos en varias

categorías.

La distinción entre litteræ communes y curiales

se parece algo haber pertenecido a un período más último, y haberse referido

algo a la manera de la entrada en el “Regesta

oficial,” las communes

que son copia en la colección general, los curiales en un volumen especial en el cual los documentos fueron

preservados cuáles por causa de su forma o de su contenido estaban parados

aparte de el resto.

Podemos

observar, sin embargo, la distinción entre el tituli y el mandamenta.

El tituli era letras de un carácter

gracioso--donaciones, favores, o confirmaciones que constituyen un “título.”

Eran

de hecho pequeños bulas y carecieron las suscripciones de los cardenales, del

rota etc., pero por otra parte, preservaron ciertas características de la

solemnidad.

Las

cláusulas imprecatory, como Nulli ergo, Si quis autem,

son generalmente incluidas, el nombre del papa al principio se escribe en

letras grandes, y la inicial es un capital ornamental, mientras que el sello

de plomo se une con los cordones de seda del rojo y del amarillo.

Según lo puesto en contraste con el tituli, el mandamenta, que eran las “órdenes,” o instrucciones, de los

papas, observa pocas formalidades, pero es más serio y expeditivo.

No

tienen ninguna cláusula imprecatory,

el nombre del papa se escribe con una mayúscula ordinaria, y el sello de

plomo se une con cáñamo.

Pero

estaba por medio de estos pequeños toros, o de litteræ, y notablemente del mandamenta,

que la administración papal del conjunto, política y religiosa, fue

conducida. Particularmente, los decretals,

en los cuales la ciencia entera de la ley de Canónica se acumula, tomaron invariable

esta forma

|

IV. FOURTH PERIOD (1198-1431)

Under Innocent III,

there again took place what was practically a reorganization of the papal chancery. But even

apart from this, we might find sufficient reason for beginning a new epoch at

this date in the

fact that the almost complete series of Regesta preserved

in the Vatican archives

go back to this pontificate.

It must

not, of course, be supposed that all the genuine bulls issued at Rome were

copied into the Regesta before

they were transmitted to their destination. There are many perfectly authentic bulls

which are not found there, but the existence

of this series of documents places the study of papal

administration from this time forward

on a new footing. Moreover, with their aid it is possible to make out an

almost complete itinerary of the medieval popes, and this

alone is a matter of considerable importance.

In light

of the Regesta were are

able to understand more clearly the working of the papal chancery. There

were, it seems, four principals bureaus or offices. At the office of the

"Minutes" certain clerks (clerici), in those days really clerics, and

known then or later as abbreviatores, drew up in precise form the

draft (litera notata) of the document to be issued in the pope's name.

Then this

draft, after being revised by a higher official (either one of the notaries or the

vice-chancellor) passed to the "Engrossing" office, where other

clerks, called grossatores or scriptores, transcribed in a

large official hand (in grossam literam) the copy or copies to be sent

to the parties.

At the

"Registration" office again it was the duty of the

clerks to copy such documents into the books, known as Regesta,

specially kept for the purpose.

Why only

some were copied and others not, is still uncertain, though it seems probable

that in any cases this was done at the request of the parties interested, who

were made to pay for the privilege which was

regarded as an additional security.

Lastly, at

the office of "Bulls," the seal,

which now bore the heads of the two apostles

on one side, and the name of the pope

on the other, was affixed by the officials called bullatores or bullarii.

At the

beginning of the thirteenth century, the great bulls, or privilegia,

as they were then usually called, with their complex forms and multiple

signatures became notably more rare, and when the papal court was

transferred to Avignon in 1309

they fell practically into disuse save for a few extraordinary occasions.

The lesser

bulls (litteræ) were divided, as we have seen, into tituli and mandamenta,

which became more and more clearly distinguished from each other not only in

their contents and formulæ but in the matter of writing.

Moreover,

the rule of authenticating the letter with a leaden seal began in

certain cases to be broken through, in favor of a seal of wax

bearing the impression of the "ring of the fisherman."

The

earliest mention of the new practice seems to occur in a letter of Pope Clement IV

to his nephew (7 March, 1265). We do not write [he says] to thee or to our

intimates under a [leaden] bull, but under the signet of the fisherman which

the Roman pontiffs

use in their private affairs. (Potthast, Regesta, no,

19,051) Other examples are forthcoming belonging to the same century.

The earliest impression of this seal now

preserved seems to be one lately discovered in the treasury of the Sancta

Sanctorum at the Lateran, and belonging to the time of Nicholas III

(1277-80). It represents St. Peter fishing with a rod and line and not as at

present drawing his net.

|

IV. CUARTO PERÍODO

(1198-1431)

En reinado de papa Inocente III, allí ocurrió otra vez cuál era prácticamente una reorganización de la cancillería papal. Pero igualar aparte de esto, nosotros pudo encontrar la suficiente razón de comenzar una nueva época en esta fecha en el hecho que la serie casi completa de Regesta preservó en los archivos de Vaticano va de nuevo a esto pontificado.

No debe, por supuesto, ser

supuesto que todos las bulas genuinos publicados en Roma fueron copiados en

el Regesta antes de que fueran

transmitidos a su destinación. Hay muchas bulas perfectamente auténticas que

no se encuentran allí, solamente la existencia de esta serie de lugares de

los documentos el estudio de la administración papal a partir de este tiempo

delantero en un nuevo pie. Por otra parte, con su ayuda es posible hacer

hacia fuera un itinerario casi completo de los papas medievales, y este solo

es una cuestión de importancia considerable.

A la luz del Regesta estaban pueden entender más

claramente el funcionamiento del cancillería papal. Había, él se parece,

cuatro oficinas de los principales u oficinas. En la oficina del “minuta” a ciertos secretarios (clerici), en esa época eran clérigo realmente, y sabido entonces o más

adelante como abbreviatores, elaboró

en forma exacta el escrito (litera notata)

del documento que se publicará en el nombre del papa.

Entonces este escrito, después de ser revisado por un

funcionario más alto (uno de los notarios o el vice-canciller) pasado a la

oficina “Engrossing”, donde otros secretarios, llamados grossatores o scriptores, transcritos en una mano oficial grande

(grossam literam) la copia o copias

que se enviarán a los partes.

En la oficina del

“registro” era otra vez el deber de los secretarios para copiar tales

documentos en los libros, conocido como Regesta,

guardado especialmente para el propósito.

Porqué solamente algunos fueron copiados y otros no, sigue

siendo incierto, aunque se parece probable que en cualquier caso esto fue hecha

a petición de los partes interesados, que fueron hechos para pagar el

privilegio que fue mirado como seguridad adicional.

Pasado, en la oficina de los “bulas,” el sello, que ahora

agujerean las cabezas de los dos apóstoles en un lado, y el nombre del papa

en el otro, fue puesto por los funcionarios llamados los bullatores o bullarii.

Al principio del siglo

13, los grandes bulas, o el privilegia,

mientras que entonces fueron llamados generalmente, con sus formas complejas

y firmas múltiples llegaron a ser notablemente más raros, y cuando la corte

papal fue transferida a Avignon en 1309 cayeron prácticamente en desuso

excepto para algunas ocasiones extraordinarias.

Las bulas menores (litteræ)

fueron divididos, como hemos visto, en

tituli y mandamenta, cuáles

hicieron cada vez más claramente distinguidos de uno a no sólo en su

contenido y formulæ pero en materia de la escritura.

Por otra parte, la regla

de autenticar el escrito con un sello de plomo comenzó en ciertos casos a ser

reemplazado a favor de un sello de la

cera que llevaba la impresión del “anillo del pescador.”

La mención más temprana

de la nueva práctica se parece ocurrir en una letra de papa Clement IV a su

sobrino (el 7 de marzo de 1265). No escribimos [él dice] al thee ni a nuestro

insinuamos debajo de bula [de plomo] de a, pero bajo sello del pescador a que

los pontífices romanos utilizan en sus asuntos privados. (Potthast, Regesta, no, 19.051) otros ejemplos son el pertenecer próximo al mismo siglo.

La impresión más temprana de este sello ahora preservado se

parece ser uno descubierto últimamente en

|

V. FIFTH PERIOD (1431-1878)

The

introduction of briefs, which occurred at the beginning of the pontificate of

Eugenius IV,

was clearly prompted for the same desire for greater simplicity and

expedition which had already been responsible for the disappearance of the

greater bulls and the general adoption of the less cumbersome mandamenta.

A brief (breve,

i.e., "short") was a compendious papal letter

which dispensed with some

of the formalities previously insisted on. It was written on vellum,

generally closed, i.e., folded, and sealed

in red wax with the ring of the fisherman.

The pope's name

stands first, at the top, normally written in capital letters thus: PIUS PP

III; and instead of the formal salutation in the third person used in

bulls, the brief at once adopts a direct form of address, e.g., Dilecte

fili--Carissime in Christo fili, the phrase being adapted to the rank and

character of the

addressee.

The letter

begins by way of preamble with a statement of the case and cause of writing

and this is followed by certain instructions without minatory clauses or

other formulæ. At the end the date is

expressed by the day of the month and year with a mention of the seal--for

example in this form: Datum Romae apud Sanctum Petrum, sub annulo Piscatoris

die V Marii, MDLXXXXI, pont. nostri anno primo. The year here specified,

which is used in dating briefs,

is probably to be understood in any particular case as the year of the

Nativity, beginning 25 December. Still this is not an absolute rule, and the

sweeping statements sometimes made in this matter are not to be trusted, for

it is certain that in

some instances the years meant are ordinary years, beginning with the first

of January. (See Giry, "Manuel de diplomatique," pp. 126, 696,

700.)

A similar want of uniformity is observed in

the dating of bulls

though, speaking generally, from the middle of the eleventh century to the

end of the eighteenth, bulls are dated

by the years of the incarnation,

counted from 25 March.

After the

institution of briefs by Pope Eugenius IV,

the use of even lesser bulls, in the form of mandamenta, became

notably less frequent. Still, for many purposes, bulls continued to be

employed--for example in canonizations (in which case special forms are

observed, the pope by

exception signing his own name, under which is added a stamp imitating the

rota as well as the signatures of several cardinals), as also

in the nomination of bishops,

promotion to certain benefices, some

particular marriage dispensations,

etc.

But the choice of the precise form of

instrument was often quite arbitrary. For example, in granting the dispensation

which enabled Henry VIII to marry

his brother's widow,

Catherine of Aragon, two forms of dispensation

were issued by Julius II, one a

brief, seemingly expedited in great haste, and the other a bull which was

sent on afterwards. Similarly we may notice that, while the English Catholic hierarchy was

restored in 1850 by a brief, Leo XIII in the

first year of his reign used a bull to establish the Catholic

episcopate of Scotland. So also

the Society of Jesus,

suppressed by a brief in 1773, was restored by a bull in 1818.

A very

interesting account of the formalities which had to be observed in procuring

bulls in Rome at the

end of the fifteenth century in contained in the "Practica"

recently published by Schmitz-Kalemberg.

|

V. QUINTO PERÍODO (1431-1878)

La introducción de breve, que ocurrió al principio del pontificado de Eugenius IV, fue incitada claramente para el mismo deseo para la mayor simplicidad y expedición que habían sido ya responsables de la desaparición de bulas mayores y de la adopción general del mandamenta menos incómodo.

Una breve (breve, es decir, “corto”) era una letra papal

compendiosa que dispensó con algunas de las formalidades insistidas previamente

encendido. Fue escrito en vitela, cerrada generalmente, es decir, doblado, y

sellado en cera roja con el anillo del pescador. El nombre del papa está

parado primero, en la tapa, escrita normalmente con mayúsculas así: PIUS PP

III; y en vez del saludo formal en la tercera persona usada en bulas , el

escrito inmediatamente adopta una forma directa de dirección, la frase Dilecte fili--Carissime in

Christo fili, que es adaptada a la fila y carácter del destinatario.

La letra comienza por el

preámbulo con una declaración del caso y la causa de la breve y de ésta es

seguida por ciertas instrucciones sin las cláusulas minatory o el otro formulæ.

En el extremo la fecha se expresa por el día del mes y del año con una

mención del sello--por ejemplo en esta forma: Datum Romae apud Sanctum Petrum,

sub annulo Piscatoris die V Marii, MDLXXXXI, pont. nostri anno primo.

. El año aquí especificado, que se utiliza en fechar el escrito,

debe probablemente ser entendido en cualquier caso particular como el año de

la natividad, comenzando el 25 de diciembre. Todavía esto no es una regla

absoluta, y las declaraciones arrebatadoras hechas a veces en esta materia no

deben ser confiadas en, porque es cierto que a veces los años significados

son años ordinarios, comenzando con primer de enero. (Véase a Giry, a “Manuel

de diplomatique,” Pp. 126, 696, 700.)

Un similar desea de uniformidad se observa en fechar de toros

sin embargo, hablando generalmente, del centro del siglo 11 al final 18 bulas

se fecha por los años de la encarnación, contados a partir del 25 de marzo.

Después de la institución

de breve de papa Eugenius IV, el uso de uniforme bulas menores, bajo la forma

de mandamenta, llegó a ser notablemente

menos frecuente. No obstante, para muchos propósitos, las bulas continuaron

siendo empleados--por ejemplo en las canonizaciones (en este caso se observan

las formas especiales, el papa por la excepción que firma su propio nombre,

bajo el cual se agrega una estampilla que imita el rota así como las firmas

de varios cardenales), como también en el nombramiento de obispos, la

promoción a ciertos beneficios, algunas dispensaciones particulares de la

unión, el etc.

Pero la opción de la

forma exacta de instrumento era a menudo absolutamente arbitraria. Por

ejemplo, en conceder la dispensación que permitió a enrique VIII casar a la

viuda de su hermano, publicó Catherine de Aragón, dos formas de dispensa

Julio II, uno un escrito, apresurado aparentemente en gran rapidez, y el otro

un toro que fue enviado encendido luego. Podemos notar semejantemente que,

mientras que la jerarquía católica inglesa fue restaurada en 1850 por un

escrito, el Leo XIII del primer año de su reinado utilizó una bula para

establecer el episcopado católico de Escocia. Tan también un toro en 1818

restauró a la sociedad de Jesús, suprimida por un escrito en 1773.

Una cuenta muy interesante de las formalidades que tuvieron que

ser observadas en procurar toros en Roma en el final del siglo 15 adentro contuvo en el “Practica” publicado

recientemente por Schmitz-Kalemberg.

|

VI. SIXTH PERIOD: SINCE 1878

Ever since

the sixteenth century the briefs have been written in a clear Roman hand upon

a sheet of vellum of convenient size, while even the wax with its guard of

silk and the impression of the fisherman's ring

was replaced in 1842 by a stamp which affixed the same devices in red ink.

The bulls,

on the other hand, down to the death of Pope Pius IX

retained many medieval features

apart from their great size, leaden seal,

and Roman fashion of dating. In

particular, although from about 1050 to the reformation the writing employed

in the papal chancery did not

noticeably differ from the ordinary book-hand familiar throughout Christendom,

the engrossers of papal bulls,

even after the sixteenth century, went on using an archaic and very

artificial type of writing known as scrittura bollatica, with manifold

contractions and an absence of all punctuation, which was practically undecipherable

by ordinary readers. It was in fact the custom in

issuing a bull to accompany it with a transsumption, or copy, in

ordinary handwriting.

This condition

of things was put an end to by a motu proprio issued by Leo XIII shortly

after his election. Bulls are now written in the same clear Roman script that

is used for briefs, and in view of the difficulties arising from transmission

by post, the old leaden seal is

replaced in many cases by a simple stamp bearing the same device in red ink.

In spite, however, of these simplifications, and although the pontifical chancery is now as

an establishment much reduced in numbers, the conditions under

which bulls are prepared are still very intricate.

There are

still four different "roads" which a bull may follow in its making.

The via di cancellaria, in which the document is prepared by the abbreviatori

of the chancery, is the

ordinary way but it is, and especially was, so beset with formalities and

consequential delays (see Schmitz-Kalemberg, Practica) that Paul III

instituted the via di camera (see APOSTOLIC CAMERA) to evade them, in

the hope of making

the procedure more expeditious. But if the process was more expeditious, it

was not less costly, so St. Pius V, in 1570,

arranged for the gratuitous issue of certain bulls by the via segreta;

and to these was added, in 1735, the via di curia, intended to meet

exceptional cases of less formal and more personal interest.

In the

three former processes, the Cardinal Vice-Chancellor, who is at the same time

"Sommista," is the functionary now theoretically responsible. In

the last case it is the Cardinal "Pro-Datario," and he is assisted

in this charge by the "Cardinal Secretary of Briefs." As the

mention of this last office suggests, the minutanti employed in the

preparation of briefs form a separate department under the presidency of a

Cardinal Secretary and a prelate his

substitute.

|

VI. SEXTO PERÍODO: DESDE 1878

Desde creación en el siglo 16 la breve es un escrito en una mano romana clara sobre una hoja de la vitela del tamaño conveniente, mientras que incluso la cera con su protector de la seda y la impresión del anillo del pescador fue substituida en 1842 por una estampilla que puso los mismos dispositivos en tinta roja.

Las

bulas, por otra parte, hasta la muerte de papa Pius IX conservaron muchas

características medievales aparte de su gran tamaño, sello de plomo, y manera

romana de fechar. Particularmente, aunque a partir de cerca de

Esta

condición de cosas fue puesta un final cerca a un motu proprio publicado por Leo XIII poco después su elección. Los

toros ahora se escriben en la misma escritura romana clara que se utiliza

para el escrito, y debido a las dificultades que se presentan de la

transmisión por correo, el viejo sello de plomo es substituido en muchos

casos por una estampilla simple que lleva el mismo dispositivo en tinta roja.

En rencor, sin embargo, de estas simplificaciones, y aunque el canciller

pontifical ahora está como establecimiento reducido mucho en los números, las

condiciones bajo las cuales los toros están preparados seguir siendo muy

intrincado.

Todavía hay cuatro diversos “caminos”

para crearan y expedir una bula. Vía

di cancellaria, en quien el documento es elaborado por el

abreviadores de la chancillería, es la manera ordinaria pero él es, y estaba

especialmente, así que sitiado con formalidades y consecuente retrasa (véase Schmitz-Kalemberg, Practica)

que Paul III instituyó vía di camera

(véase

En

los tres procesos anteriores, el Vice-Chancellor

cardinal, que es al mismo tiempo “Sommista,” ahora es el funcionario

teóricamente responsable. En el caso pasado es el “Pro-Datario cardinal,” y a

la “secretaria cardinal del escrito lo asiste a esta carga.” Pues la mención

de esta última oficina sugiere, el minutanti empleó en la preparación de la

forma del escrito un departamento separado bajo presidencia de una secretaria

cardinal y de un prelado el suyo substituto

|

SPURIOUS BULLS

There can

be no doubt that

during a great part of the Middle Ages papal and other

documents were fabricated in a very unscrupulous fashion. A considerable

portion of the early entries in chartularies

of almost every class are not only open to grave suspicion, but are often

plainly spurious. It is probable, however, that the motive for their

forgeries was not criminal. They were prompted by the desire of protecting monastic property against

tyrannical oppressors who, when title deeds were lost or illegible, persecuted the

holders and extorted large sums as the price of charters of confirmation.

No doubt,

less creditable motives--e.g., an ambitious

desire to exalt consideration of their own house--were also operative, and

while lax principles in this matter prevailed almost universally it is often

difficult to distinguish the purpose for which a papal bull was forged.

A famous early example of such forgery is

supplied by two papyrus bulls which profess to have been addressed to the Abbey of St. Benignus

at Dijon by Popes John V (685) and

Sergius I (697),

and which were accepted as genuine by Mabillion and his confrères.

M. Delisle has,

however, proved they are

fabrications made out of later bull addressed by John XV in 995 to

Abbot William,

one side of which was blank. The document was cut in half by the forger and

furnished him with sufficient papyrus for two not unsuccessful fabrications.

Though deceived in this one instance, Mabillion and his successors, Dom Toustain and Dom Tassin, have

supplied the most valuable criteria by the aid of which to detect similar

fabrications, and their work has been ably carried on in modern times by

scholars like Jaffé, Wattenbach, Ewald, and many more. In particular a new

test has been furnished by the more careful study of the cursus, or

rhythmical cadence of sentences, which were most carefully observed in the authentic bulls of

the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. It would be impossible to go into

details here, but it may be said that M. Noæl Valois, who first investigated

the matter, seems to have touched upon the points of primary importance.

Apart from this, forged bulls are

now generally detected by blunders in the dating clauses

and other formalities. In the Middle Ages

one of the principal tests of the genuineness of bulls seems to have been

supplied by counting the number of points in the circular outline of the

leaden seal or in the

figure of St. Peter depicted on it.

The bullatores

apparently followed some definite rule in engraving their dies. Finally,

regarding these same seals, it may

be noted that when a bull was issued by a newly elected pope before

his consecration,

only the heads of the Apostles were

stamped on the bulla, without the pope's name. These

are called bullæ dimidiatæ.

The use of

golden bullæ (bullæ aureæ), though adopted seemingly from the

thirteenth century (Giry, 634) for occasions of exceptional solemnity, is too

rare to call for special remark. One noteworthy instance in which a golden seal was used

was that of the bull by which Leo X conferred

upon King Henry VIII

the title of Fidei Defensor.

|

BULAS FALSOS

No puede haber duda que durante una mayor parte de

las edades medias papales y otros documentos fueron fabricados en una manera

muy sin escrúpulos. Una porción considerable de las entradas tempranas en

chartularies de casi cada clase está no sólo abierta a la suspicacia grave,

pero es a menudo llano falsa. Es probable, sin embargo, que el motivo para

sus falsificaciones no era criminal. Fueron incitadas por el deseo de

proteger la propiedad monástica contra los opresores tiránicos que, cuando

los hechos de título eran perdidos o ilegibles, perseguido los sostenedores y

las sumas grandes extorted como el precio de cartas de la confirmación.

Ninguna duda,

motivos menos encomiables--e.g., un deseo ambicioso de exalt la consideración

de su propia casa--estaba también el operario, y mientras que prevalecieron

los principios flojos en esta materia casi universal es a menudo difícil

distinguir el propósito para el cual un toro papal fue falseado.

Un ejemplo temprano famoso de tal falsificación es

proveído por dos bulas del papiro que profesen haber sido tratados a la

abadía de St. Benignus en Dijon por papas Juan V (685) y Sergius I (697), y

que fueron aceptados como genuinos por Mabillion y sus confrères.

El M. Delisle tiene, sin embargo, probado son

fabricaciones hechas fuera de una bula más último tratado por Juan XV en 995

al abad Guillermo, un lado de quien estaba en blanco. El documento fue

cortado adentro a medias por el forger y equipado te con el suficiente papiro

para dos fabricaciones no fracasadas. Engañado sin embargo en este un caso,

Mabillion y sus sucesores, Dom Toustain y Dom Tassin, han proveído los

criterios más valiosos por la ayuda de la cual detectar fabricaciones

similares, y de su trabajo ha sido continuada capaz en épocas modernas por

los eruditos como Jaffé, Wattenbach, Ewald, y muchos más. Particularmente una

nueva prueba ha sido equipada por el estudio más cuidadoso del cursus, o la

cadencia rítmica de las oraciones, que fueron observadas lo más cuidadosamente

posible en las bulas auténticos de los siglos 13 y 14. Sería imposible entrar

los detalles aquí, pero puede ser dicho que el M. Noæl Valois, que primero

investigó la materia, se parece haber rozado los puntos de la importancia

primaria.

Aparte de esto, las bulas falsas ahora son detectadas

generalmente por equivocaciones en las cláusulas que fechan y otras

formalidades. En las edades medias una de las pruebas principales de la

autenticidad de toros se parece haber sido proveído contando el número de

puntos en el contorno circular del sello de plomo o en la figura de St. Peter

representada en él.

Los bullatores

siguieron al parecer una cierta regla definida en el grabado de sus dados.

Finalmente, con respecto a estos mismos sellos, puede ser observado que

cuando un toro fue publicado por un papa nuevamente elegido antes de su

consagración, sólo las cabezas de los Apostoles fueron estampadas en la bula,

sin el nombre del papa. Éstos se llaman bullæ dimidiatæ.

El uso de la bula de oro (bullæ aureæ), aunque adoptado aparentemente a partir del siglo 13 (Giry,

634) para las ocasiones de la solemnidad excepcional, es demasiado raro

llamar para la observación especial. Un caso significativo en el cual un

sello de oro fue utilizado era la bula por el cual el Leon X confirió sobre

el rey enrique VIII el título de Defensor de

|

|

| 1529, agosto, 6. Roma Breve de Clemente VII perdonando a los que se hallaron y consintieron en el Saco de Roma. Archivo General de Simancas AGS. E. 848, 5-6 |

|

| Bula papal de nombramiento de Obispo de Alcala |

|

| Bula papal de nombramiento de Obispo de Alcala |

Publication information

Written

by Herbert Thurston. Transcribed by M. Donahue.

The Catholic

Encyclopedia, Volume III. Published 1908. New York New

York

Bibliography

Ortolan in

Dict. de theol, cath., II, 1255-63--see remark, page 49, col. 2; Grisar in

Kirkenlex, II, 1482-95; Giry, Manuel de diplomatique (Paris, 1894), 661-704--an

excellent summary of the whole subject; Pflugk-Harttung, Die Bullen der Papste

(Gotha, 1901)--mainly concerned with the period before Innocent III; Melampo in

Miscellanea di Storia e Cultura Ecclesiastica (1905-07), a valuable series of

articles not too technical in character, by a Custodian of the Vatican

Archives; Mas-Latrie, Les élementes de diplomatique pontificale in Revue des

questions historiques (Paris, 1886-87), XXXIX and XLI; De Kamp, Zum papstlichen

Urkundenvessen in Mittheilungen des Inst. f. Oesterr. Geschictesforschung

(Vienna, 1882-83), III and IV, and in Historiches Jahrbuch, 1883, 1883, IV;

Delisle, Des régitres d'Innocent III in Bibliothéque de l'écoles des chartres

(Paris, 1853-54), with many other articles; Bresslau, Handbuch der

Urkundenlehre (Leipzig, 1889), I, 120-258; De Rossi, Preface to Codices

Palatini Latin Bib. Vat. (Rome, 1886); Berger, preface to Les régistres

d'Innocent IV (Paris, 1884); Kehr and Brockman, Papsturkunden in various

numbers of the Göttinger Nachrichten (Phil. Hist. Cl., 1902-04); Kehr, Scrinium

und Palatium in the Austrian Mittheilungen, Ergènzungaband, VI; Pitra, Analecta

Novissima Solesmensia (Tusculum, 1885), I; Schmitz-Kahlemberg, Practica (1904).

Among earlier works mention may be made of Mabillion, De Re Diplomatica (Paris , 1709), and the Nouveau traité de diplomatique by

the Benedictines of Saint-Maur (Paris

Early

Bulls--Bresslau, Papyrus und Pergament in der papstlichen Kanzlei in the

Mittheilungen der Instituts für Oest. Geschictsforschung (Innsbruck, 1888), IX;

Omont, Bulles pontificales sur papyrus in Bibl. les l'école des chartes (Paris,

1904), XLV; Ewald, Zur Diplomatik Silvesters II in Neues Archiv (Hanover,

1884), IX; Kehr, Scrinium und Palatium in the Austrian Mittheilungen,

Ergènzungaband, (Innsbruck, 1901) VI; Kehe, Verschollene Papyrusbullen in

Quellen und Forschungen aus italienischen Archiven (Rome, 1907), X, 216-224; Rodolico,

Note paleografiche e diplomatiche (Bologna, 1900).

For

facsimiles both of early bulls and their seals, the great collection of

Pflugk-Harttung, Specimena Selecta Chartarum Pontificum Romanorum (3 vols., Stuttgart

On the cursus it will be sufficient to mention

the article of Noæl Valois, Etudes sur le rythme des bulles pontificales in

Bibl de l'école des chartes (1881), XLII, and De Santi, Il Cursus nella storia

litter. e nella liturgia (Rome, 1903)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario